Overview: what is Domain-Driven Design (DDD)?

Why does complex software sometimes feel like a collection of loose features rather than a coherent whole that truly reflects the organisation’s domain? Domain-Driven Design, commonly abbreviated to DDD, is an approach designed to solve exactly that problem.

DDD is a mindset for software in which the domain—the business problem you’re solving—takes centre stage. It’s not a framework or library, but a set of principles, patterns and language guidelines that help align code, architecture and business knowledge.

Key take-aways in this article:

A clear definition of Domain-Driven Design and its purpose

An explanation of strategic patterns such as domains, sub-domains and bounded contexts

A tour of tactical building blocks like entities, value objects, aggregates, repositories and domain events

The importance of a ubiquitous language and close collaboration between domain experts and developers

How DDD relates to microservices, legacy monoliths and modern stacks such as Laravel

Practical guidelines for deciding when DDD does and doesn’t make sense

By the end you’ll have a concrete vocabulary and be able to decide—based on sound reasoning—how and to what extent to apply DDD in your own project.

So what exactly is Domain-Driven Design?

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) is an approach to designing and building software in which the business problem domain takes centre stage. The domain is the subject matter your software addresses, for example wealth management, student housing, e-commerce or logistics.

The essence of DDD is that you don’t start with technical layers but with understanding and modelling the domain itself. You then translate that model into software so that the structure of your code mirrors the structure of the business problem. DDD therefore focuses on language and collaboration as much as on architecture and design.

Crucially, DDD isn’t a plug-and-play framework. It’s a collection of concepts and patterns you can combine in various ways. You can apply DDD within a Laravel monolith, across a set of microservices or even in a legacy system you plan to refactor step by step into more logical components.

A friendly video introduction that visualises many of these concepts is this talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pMuiVlnGqjk. It dovetails nicely with the terms expanded upon in this article.

Why did DDD emerge?

DDD arose from the observation that many software projects fail or become unnecessarily complex, not because of technical limitations but due to misunderstandings between domain experts and developers. The business uses certain words, IT uses different ones, and somewhere in translation the essence gets lost.

Typical symptoms include:

The same term means something different in different teams

Business rules are scattered across controllers, services and UI code

Changes in the domain trigger unpredictable side-effects in the code

No one can explain why the system behaves the way it does anymore

DDD aims to bridge this gap by tying the domain language directly to the software structure. The benefit is that domain knowledge isn’t just in people’s heads but is explicitly and consistently anchored in the model and the code.

Strategic DDD concepts: domains, sub-domains and bounded contexts

At a strategic level, DDD helps you slice large, complex systems in a logical way. It does so with notions like domain, sub-domain and bounded context. These concepts determine where particular models and definitions apply—and where they don’t.

A domain is the overall problem space your application addresses. For a property platform, for example, that could be residential letting, including everything from rental agreements and payments to matching supply and demand and compliance with regulations.

Within that broad domain you distinguish sub-domains: logical sub-areas with their own goals and terminology, such as tenancy management, payments or the client portal. Each sub-domain has different priorities and complexity, and DDD encourages you to model the core sub-domains with the highest strategic value most thoroughly.

The term bounded context is the boundary around one specific model and one specific language. Within a bounded context, terms have a sharp, consistent meaning. Outside that context the same term may mean something else. A classic example is customer: in a billing context it has different attributes and rules than in a marketing context, even though both refer to the same person.

Bounded contexts have relationships with one another. You can make these explicit in context maps showing how models connect, which teams are responsible and through which integrations data is exchanged. Patterns such as conformist, anti-corruption layer and shared kernel help structure how tight or loose those couplings are.

On this strategic level, DDD aligns neatly with modern architectural styles like microservices. Each microservice can represent one bounded context with its own model and data store. But DDD isn’t limited to that; you can apply the same ideas within a modular monolith—for instance, where different Laravel modules or packages each form a bounded context.

Ubiquitous language: a shared vocabulary within the context

A fundamental part of DDD is the ubiquitous language—the shared, ever-present vocabulary used by both developers and domain experts. This language doesn’t emerge from documents but from conversations, workshops and iterative modelling.

The rules are simple yet strict:

Terms in the ubiquitous language get a precise definition within their bounded context

Those terms appear in code—in class names, methods and modules

When the language changes, the model and ultimately the code must change with it

The practical impact is huge. If the domain says there is a contract request, a draft contract and a final contract, you’ll see those exact concepts in your types and services. This makes discussions about behaviour concrete and prevents invisible logic from creeping into generic names like data, item or record.

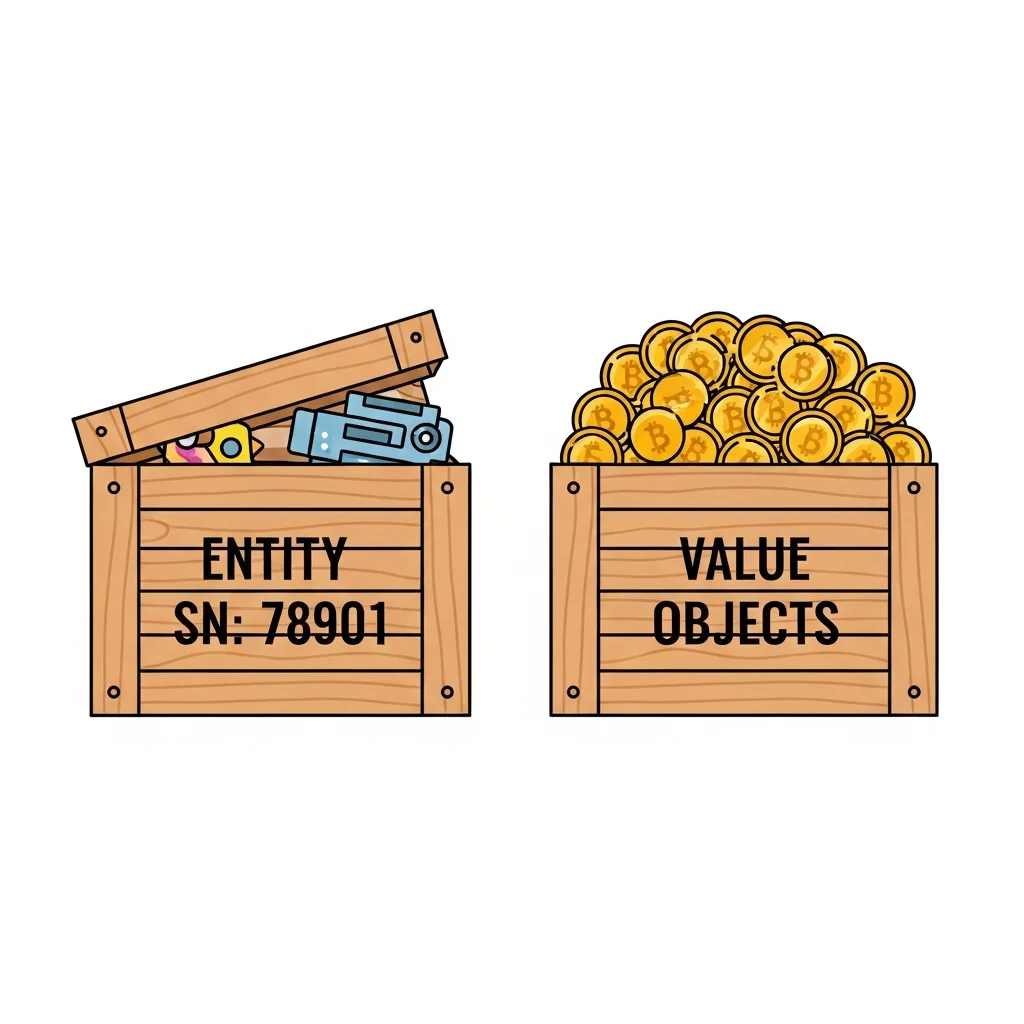

Tactical DDD building blocks: entities, value objects and aggregates

In addition to strategic patterns, DDD offers tactical building blocks that help translate the domain model into code. The best-known concepts are entities, value objects, aggregates, repositories and domain events. These ideas are language-agnostic and work perfectly in PHP or Laravel, for instance.

An entity is an object with a stable identity over time. Its state may change, but it remains the same entity. A tenant, an order or a user are typical entities. The identity is usually represented by an id that is also used in references and relationships.

A value object represents a value without its own identity. Examples include money amounts, periods, addresses or email addresses. Value objects are immutable: if a value changes you create a new object. They are compared by value rather than by id, making them ideal for encapsulating domain logic such as validation rules or calculations.

Aggregates are clusters of entities and value objects that you treat as one consistent whole. Within an aggregate there is a single central entity—the aggregate root. Access to other parts of the aggregate always goes through that root, enforcing consistency rules, especially when you deal with transactions and concurrency.

A simplified PHP-style example might look like this:

final class Order

{

private OrderId $id;

/** @var OrderLine[] */

private array $lines = [];

private OrderStatus $status;

public function addLine(ProductId $productId, Quantity $quantity): void

{

if (!$this->status->isDraft()) {

throw new DomainException('Only draft orders can be modified.');

}

$this->lines[] = new OrderLine($productId, $quantity);

}

public function confirm(): void

{

if ($this->status->isConfirmed()) {

throw new DomainException('Order already confirmed.');

}

$this->status = OrderStatus::confirmed();

// Here you could raise a domain event, e.g. OrderConfirmed

}

}

In this example you can spot several DDD patterns. `Order` is the aggregate root, `OrderLine` is a subordinate component, and classes like `ProductId`, `Quantity` and `OrderStatus` can be modelled as value objects with their own rules.

Repositories and domain events

Repositories form the bridge between the domain model and the underlying data store. In DDD they formalise a domain collection with query methods that fit the domain. Instead of generic database calls, you define interfaces such as `OrderRepository` with methods like `byId`, `byCustomer` or `save`. The implementation may use, say, Laravel’s Eloquent, but those details stay outside the domain.

Domain events are messages indicating that something significant has happened in the domain. They allow loosely coupled parts of the domain—and the wider system—to react without hard dependencies. Think of events like `OrderConfirmed`, `CustomerRegistered` or `PaymentFailed`. These events can be handled within the same bounded context or across context boundaries via integrations or messaging.

Together, these tactical building blocks create a model that sits close to the business while remaining technically solid. They make explicit where behaviour belongs and where data is merely a representation of domain concepts—never the other way around.

What is Domain-Driven Design in simple terms?

Domain-Driven Design is a way of designing software by starting from the business problem and the organisation’s language. You first build a clear domain model and then shape your code and architecture around it instead of the other way round. As a result, the software aligns better with how the business actually works.

Is DDD a framework or a tool I can install?

No, DDD isn’t a framework, library or specific tool. It’s a collection of principles, patterns and mental models. You can apply DDD in all sorts of technical environments—for example within a Laravel application, a microservices landscape or even a legacy monolith. The tools you use are secondary to how you model the domain.

When does it make sense to use Domain-Driven Design?

DDD becomes particularly valuable once your domain grows complex and contains many business rules. Experience shows that projects in finance, legal, healthcare, logistics or property often benefit because of intricate processes and regulations. For very simple CRUD applications DDD can be overkill; a lighter architectural pattern is usually sufficient.

How does DDD relate to microservices?

DDD and microservices complement each other but aren’t the same. Microservices are about splitting a system into independently deployable services. DDD helps you decide where to draw those boundaries—typically along bounded contexts. Teams combining the two often find their services align better with real domain responsibilities and are less arbitrarily sliced.

Can I apply DDD in an existing legacy monolith?

Yes you can, and it’s actually a common scenario. A practical approach is to first identify the domains, sub-domains and bounded contexts and then restructure modules or components step by step using DDD principles. Teams often start with a core sub-domain that causes the most pain so they quickly experience how the new structure brings clarity and stability.

How do I get started with DDD in my team?

A good first step is to organise joint sessions with domain experts and developers, such as event-storming workshops or modelling sessions with whiteboards. Map out processes, events and terms, then translate the most important concepts into entities, value objects and aggregates in code. Teams that take this incremental approach find the ubiquitous language grows organically and discussions about behaviour become more concrete and productive.

Do I need full organisational buy-in to use DDD?

Full buy-in helps, but it isn’t strictly required. You can apply DDD within a single team or bounded context and demonstrate the benefits from there. In practice, a small, well-modelled domain often becomes a showcase for the rest of the organisation. Successful cases then naturally create more support among other teams and stakeholders.